Our Blue Planet Up Close and Personal

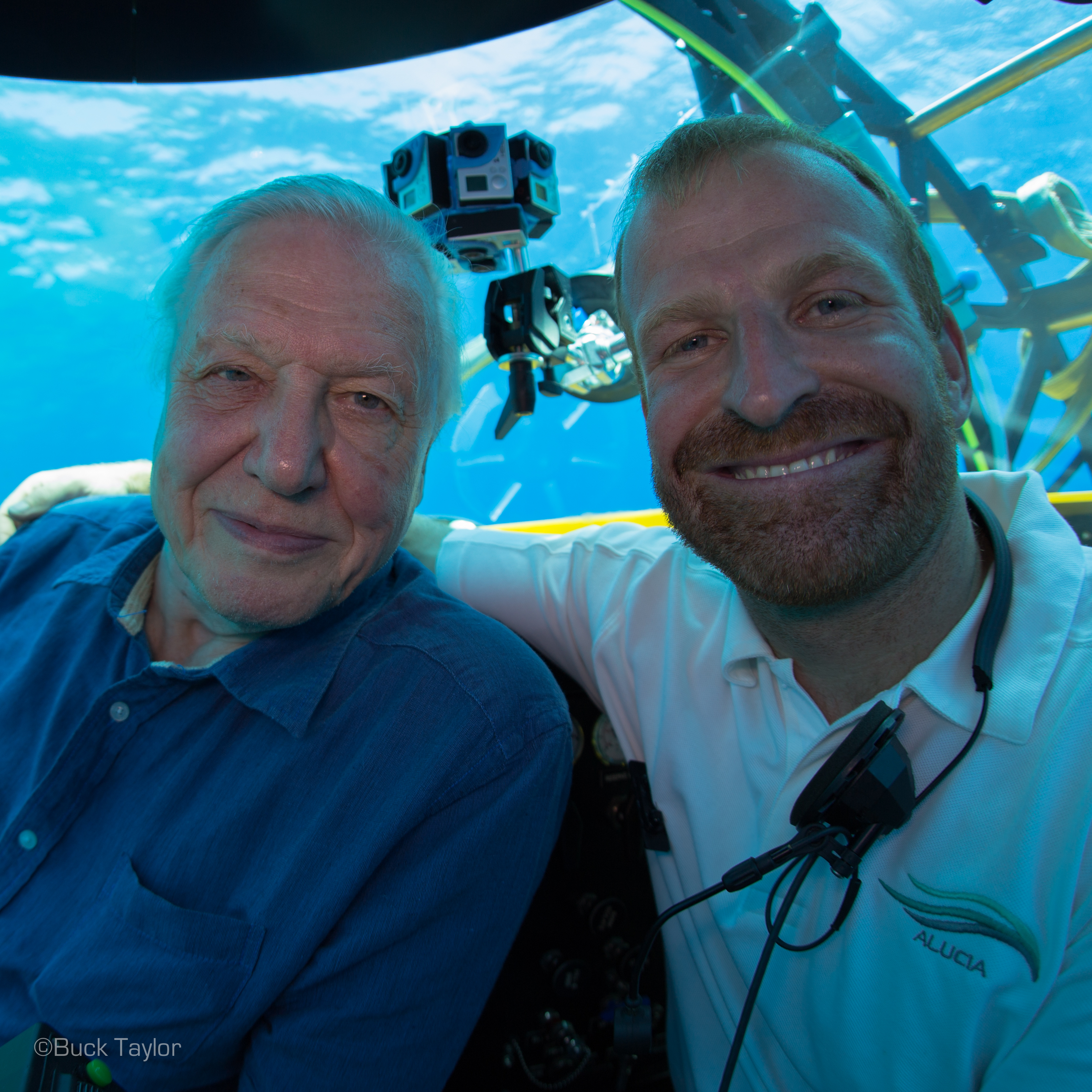

Documentaries such as Blue Planet and The Great Reef have brought new wonder and awareness into our living rooms. Former Royal Navy underwater bomb disposal expert turned submarine pilot Mark Taylor now explores the planet's oceans as an integral part of the subsea documentary filmmaking community. He has seen eels dip into lakes 750 metres under the ocean, witnessed mud volcanoes on the sea floor and come face to face with a giant squid 10 metres long with eyes the size of basketballs. He also spent many hours submersed with his childhood hero, Sir David Attenborough, filming for Blue Planet II and describes the comraderie and lifelong bond that resulted from it.

PERSONAL COMMENT

Imagine how you would feel if you came face to face with your childhood hero and spent hours together 300 metres underwater in a three-seater submarine filming for Blue Planet II. Mark shares his deep-sea experience doing just that and the lifelong bond that subsequently developed with Sir David Attenborough. It's a touching story and describes an experience to cap all others in Mark's extraordinary career to date. Mark's joy of discovering new species in unexplored oceanic depths was quite infectious, I hope you agree.

You can check out some more of Mark's stunning underwater images at Instagram - Mark (Buck) Taylor

You may remember listening to Mark in episode 23 where he talks about being part of the Royal Navy UK submarine rescue sent to ettempt to save the lives of the submariners on the Russian nuclear submarine The Kursk, back in 2000. If you haven't heard it, listen now - Access Denied: The Kursk Submarine Rescue Story.

Previous episode

[Episode 39] - Operation Clinker - In October 1988, the Hong Kong police executed Operation Clinker and achieved the largest ever drug haul in Hong Kong history. Bill Renwick was undercover with the team of four who heroically overcame two of the drug syndicate on a ketch somewhere on the edge of the South China Sea. Think of The French Connection meets Popeye with a sprinkling of Keystone Kops, and you have all the ingredients for this fabulous story.

Next episode

[Episode 41] - Grounded by an Autobiographic Memory - Do you pride yourself on your infallible memory? Well think again. Memories about ourselves and the events of our lives are nurtured by our Autobiographic Memory and, shockingly, it turns out that it is unreliable by design. Our story centres on Brian Williams, America's one-time No. 1 news anchor. He reported from the front line in 2003 at the start of the Iraq War when the Americans were hunting down weapons of mass destruction. He braved Chinook helicopter missions within firing distance of enemy lines and returned to America a hero.

Twelve years later, it all came crashing down. We find out why with some help from Dr Andrew Dunn, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Nottingham Trent University, with specific research interests in perception, developmental psychology and memory. We discover what really happened to Brian Williams and reveal the wonder of Autobiographic Memory, its fallibility and its role in helping us to flourish as social animals.

We love receiving your feedback - head over to https://www.battingthebreeze.com/contact/

Thanks for listening!

[00:00:00] Mark Taylor: We've mapped the moon many many times. We've mapped Mars. We know every inch of Mars. We have mapped just over 10% of our oceans and we've visited either with a remotely operated vehicle or a manned submersible only 0.5% of our oceans. We know more about Mars than we do about our own planet.

[00:01:10] Steve: Back in episode 23 I spoke to Mark Taylor, 11 years Royal Navy underwater bomb disposal expert, followed by a further 3 years attached to the UK submarine rescue team. And it was on that duty that Mark was part of the attempt to rescue the trapped submariners in the Russian nuclear submarine The Kursk back in 2000. It's an incredible story, please check it out. Mark was obsessed with the oceans, and in particular, what lay underneath. This is what he had to say back in that episode.

[00:01:47] Mark Taylor: You could find me annoying the local dive shop from about 10 years old, trying to convince them to take me diving, which eventually they did. I moved to Lulworth Cove in Dorset and pretty much every weekend, rain, shine, summer, winter, you could find me bobbing around the rocks and looking at life under the water. And to me it just opened up a whole new world. I loved the ocean. I grew up watching Jacques Cousteau, David Attenborough and it was those sort of documentaries that just started my love of the ocean.

[00:02:27] Steve: So it was no surprise when Mark left the Royal Navy that his life remained fully submersed in the ocean. He started a new phase of his career in submarine rescue training, travelling all around the world, sharing his expertise. During one of these trips in 2007...

Hello commercial filming

[00:02:47] Mark Taylor: By chance I met a guy called Patrick Lahey who at the time had just started a small company in the US called Triton Submarines, just at the start of an age where private investors were getting interested in ocean research, ocean conservation, and so suddenly there was an influx of small submersibles, deep submersibles and this industry has started growing and I saw an opportunity not to completely leave submarine rescue, but to basically take two routes. I ended up on a ship called the Alucia which was funded by Ray Dalio who's one of the big hedge fund owners. And we had two submersibles on board. The ship didn't have a home port so we would literally sail everywhere. I managed to dive in every ocean, many of the seas literally all around the world.

[00:03:51] Steve: What was the motivation for Ray Dalio to spend all this money?

[00:03:55] Mark Taylor: It wasn't for pleasure. Ray Dalio loved ocean science and he loved ocean conservation but he hated scientists who would sit there document something in the little black book it would shut. They'd disappear and you'd never see it again. And so his vision was to take that science and give it to the world And so we'd merge media teams with science teams, go out, do the science but document it at the same time and turn it into stories which, for the layman and I'm not a scientist, it suddenly became interesting and personal. One of the biggest documentaries we did on board was all the deep work for Blue Planet II and that started the plastic revolution. So without that link between the scientists and the media, it would've just been lost.

[00:04:57] Steve: That's interesting. These documentaries appear on our screens. We binge watch them in a flash and then they're gone, aren't they? We're pretty unaware of the time and hence cost that went into the making.

[00:05:11] Mark Taylor: Absolutely, yeah.

[00:05:12] Steve: Give us an idea of the timescales involved making, say, Blue Planet II.

[00:05:18] Mark Taylor: We were filming for three and a half years and it was another year in edit. We travelled all over the world and people question why it takes so long. Some of these events that we were trying to capture only happen once a year, but because you have a ship that can only do 12 to 15 knots, you literally can't be everywhere. And you try and be as environmentally friendly as possible and you try and go from job to job to job without doing huge transits for no reason. And so with travel time and everything else it's literally three and a half years to do Blue Planet II.

[00:05:58] Steve: And what about the submarines themselves, because they're quite different from how we might normally imagine a submarine, I guess?

Manned subs

[00:06:07] Mark Taylor: Technology's changed the whole sub-sea and manned sub industry. These submersibles are acrylic hulled, so a completely clear hull. The people sit inside, the thickness of the spheres about seven inches those ones on the Alucia would go down to a 1000 meters - 3300 feet - and it's literally like being sat here. There's no difference. You can take a flask of coffee, some sandwiches, and many of the science and media dives we'd be in for 8 to 10 hours at a time with two submersibles, one normally doing the science work and the other one filming. Three people to fit in: one pilot, and normally you'd have a scientist or a cameraman. The camera systems we'd have, we were filming in 8K at the time for Blue Planet. In terms of tooling, we'd have hydraulic manipulators so you could take samples. We had a manufacturing area on board the ship, so if scientists or filmmakers came on board and they had a good idea, we could manufacture parts and design certain equipment to try and make things work.

[00:07:20] Steve: And thinking about the type of work these submersibles are used for, presumably they're more responsive than a... more typical submarine?

Submarine manoeuvrability

[00:07:30] Mark Taylor: Yeah, the subs themselves are very manoeuvrable. They're fitted with six thrusters, so you can rotate and up and down and go forwards, not particularly fast. They'll go about three knots. They're fitted with robotic arms. With a small arm inside, whatever you do with that arm , the main arm outside copies your arm. And the arm itself can be as gentle as picking up an egg or at full reach, which is over two meters, will pick up almost 200 kilos. So it's super strong but at the same time can be amazingly gentle. Yeah.

[00:08:08] Steve: And you're the submarine pilot, but your job is to do the picking as well?

The submarine pilot

[00:08:14] Mark Taylor: Yes, the pilot manouvres the sub, but he also operates the robotic arms and manipulates the science equipment or the cameras. And when you're doing science work, you'll normally have a scientist inside and a camera person and they're advising you what they'd like to do, and you do your best to achieve what they want. And then on the camera side of things, you are normally fitted with two cameras, one wide angle and one macro. And so you are flying the sub, but you're also looking at the monitors because the cameraman's...you can see what he's filming and you're basically putting the submersible in the right place to get the best shot and positioning lights and everything else to get that perfect shot.

[00:09:03] Steve: How much do they weigh?

[00:09:05] Mark Taylor: The subs weigh about 8 tonnes and if you go and look at Blue Planet II, episode 2, you'll see some of the shots. We're filming critters which are about an inch long with an 8-tonne submersible and so you've gotta be very precise. And it's an art. Because we spend so much time in the water with the camerman and yourself positioning, you end up getting this unconscious link where you can put the sub in exactly the right position without even talking. You know, you're doing 8 to 10 hours a day in the dark for seven days a week for normally a month at a time. And so you... get these very strong bonds and it's, yeah, it's strange but amazing when it all clicks.

[00:09:57] Steve: So you're the guy who picks up these things that could be as delicate as an egg. So what are you like when you're in the kitchen at home? Are you dexterous with your eggs or are you a bit clumsy or...

[00:10:08] Mark Taylor: I'm better with the manipulator that I am in the kitchen with my hands, yes...

[00:10:15] Steve: As a pilot of these high tech manned subs, there's clearly a lot to do and each session can last for hours. Lots of responsibility, risk. So what is it that Mark actually enjoys about piloting?

[00:10:30] Mark Taylor: The best part of the job for me is when I climb in and you shut the hatch, and you call it dogging it, so twist a handle, it puts the pins out and locks a hatch in. And for me, that's just the best feeling ever. You're cutting yourself off from the outside world. It goes quiet because you can't hear the ship noises anymore ...you lose wifi, which is great 'cause you can't get emails, and then you get in the water, which is amazing; you know, the colours, all the different blues and turquoises. And as you descend you start losing the different colours because of the way the lights filtered through, and then eventually at about 150.. 200 meters, it will go completely dark and you keep descending depending on what you're gonna do. But it's a time machine.

[00:11:18] Steve: What about food?

[00:11:20] Mark Taylor: We'll take lunch with us, we'll take drinks with us. Occasionally you have to wiggle your toes and jump up and down like you would on the airplane, but it certainly doesn't drag. They are time machines.

[00:11:33] Steve: So, describe to me how it feels sitting in such a small sub.

[00:11:38] Mark Taylor: It is literally just like sitting in a room. The subs, believe it or not, are quite warm. When you get down to about a thousand meters all over the world it's about 1.6 degrees. You know, it's pretty standard across the globe. But the acrylic is so thick and it's such a good thermal barrier that the temperature remains constant. we do have air conditioners in there which takes out the humidity, because you've got all your electronics and things, so it literally is like sitting here.

[00:12:12] Steve: Can you stand up?

[00:12:14] Mark Taylor: I can stand up cause I'm a dwarf. You'd probably struggle

[00:12:19] Steve: There's probably also a weight limit isn't there?

[00:12:21] Mark Taylor: Um... but It's huge. I think it's like over 150 kilos, so yeah...

Mark's favourite places

[00:12:27] Steve: Okay... and of course you'll have seen some amazing sights down there. Can you pick out one or two of your favourites for us?

[00:12:35] Mark Taylor: Yeah, I've been very lucky because I've managed to dive all over the world. But I think there's two areas that I just love. They're just unbelievable. The first one is in the Gulf of Mexico with the brine pools and the methane vents, you can see it on Blue Planet II, where you are watching eels dip into a lake, which is at 750 meters under the ocean, and it has a beach and you can see waves rolling up the beach. It's just incredible. You're looking at this thing and you're like, "How does this exist?" And it's just super saline water, which sits in pools on the bottom of the ocean and produces lakes.

[00:13:18] Steve: Yeah, it's almost impossible to imagine that. What was the other one?

[00:13:23] Mark Taylor: And then where we're over this mud volcano giving off these big methane bubbles and I'm filming the other sub coming through, it's literally like a sci-fi movie, War of the Worlds. These big bubbles are going up and the subs coming through and you have to pinch yourself because... it doesn't feel real. The fact that you've got seven inches of acrylic between you and the outside and there's no pressure, sometimes you sort of forget where you are, you know, you're consciously taking it in but the reality of where you are, it's so removed.

Giant squid

[00:14:20] Steve: Now, tell us about your experience with a giant squid.

[00:14:24] Mark Taylor: Yeah. The whole industry is strange because you have hours and hours of boredom, with tiny segments of extreme excitement, because we are going down to new areas that nobody has ever seen before, we have no idea what's gonna be down there. We were the first team to film Giant Squid off Japan, which was incredible. We spent a month off Chichijima Islands, which are off the east coast of Japan. So a month diving two subs every day, and it wasn't from the second to last day of the charter that we managed to film 20 minutes of footage, where a giant squid came to the front of the sub. We had another squid as bait, and it came in and it just sat on the front of the sub, 10 meters long, eyeballs the size of basketballs and it was the first time that anybody'd seen the giant squid in its natural habitat.

[00:15:23] Steve: It must be such an unbelievable privilege to see some of these wonders, and before anybody else has seen them.

[00:15:32] Mark Taylor: We are so lucky, we've seen so much. I'll give you an example of how little we know: We were in Papua New Guinea and in one dive we identified over 20 new species of fish. The last time I was in the Galapagos Islands, we found two new species of shark. We'll go down with scientists who are experts in their field, you know they may have been studying for 20.. 30 years, but very often they'll turn around and look at us and say, "Wow, have you seen that before?" And you'll say, "Oh yeah, that's a so-and-so so-and-so", and they'll go, "My God, I've never seen that". And this happened to me fairly recently in the Azores with a scientist called Edi Widder who studies bioluminescence, so it's the flashing of lights underwater and in the water. And with the latest cameras, we could really capture these events so well and so precisely. And, she's in her sixties, and within two dives she said it... basically blew all of her studies out of the water,

[00:16:42] Steve: that's absolutely mad..

[00:16:44] Mark Taylor: Yeah. And it is sad because you sort of start to take it for granted a little bit until somebody like that comes along and they're like, "Wow", and you're like, "Oh, really? We see those all the time".

Human bonding

[00:17:02] Steve: Now, you mentioned earlier the bond that you build up in a sub with, I think you were referring to the cameraman in that case, but presumably you build a special bond with anyone who you spend hours and days and weeks with at a time. Tell me a little bit about that.

[00:17:18] Mark Taylor: Yeah, being inside this acrylic sphere is very small, very intimate. You get to know people very, very quickly. I've got a great relationship with a lady called Orla Doherty who's... a BBC producer, produced The Deep episode for Blue Planet II, and the cameraman Gavin Thurston. And it's amazing. You... you're in that sub, you're all working, but very often it's complete silence. You're concentrating on what's going on but there's a link. It's not like the Director's shouting at you to do this, do that, and the cameraman's asking you to position. It's surreal because you sort of almost morph into one person and it just flows, it just happens.

[00:18:05] Steve: It turns out that sometimes, it doesn't happen.

[00:18:10] Mark Taylor: We get pilots who you'll put in with certain people and it just doesn't work and you just have to switch them out. ' It's definitely a personality thing. And running the teams, that was part of my job to try and watch what was happening and making sure that the scientists were getting what they wanted and the camera people were getting what they wanted. But when you get that right team together, it just flows and it's... such a pleasure to be involved in.

[00:18:39] Steve: So let's say you're walking along Oxford Street, and you bump into one of them. Is that special bond only while you're down in the sub, or are you feeling it at that point?

[00:18:49] Mark Taylor: Yeah. No, absolutely. Something happens and it just changes. You've got this unwritten, unspoken feeling. It's very strange, but amazing. Yeah.

Meeting David Attenborough

[00:19:03] Steve: So, as it turns out, that bond could be with anyone; the cameraman, the scientist, the TV producer, anyone who happens to be down in that sub with you for hours and days and sometimes weeks. Now, imagine if one of those people turned out to be your childhood idol. And in this case, David Attenborough.

[00:19:27] Mark Taylor: I was at the stage now where he'd narrated many of the documentaries that I've been involved in. And then, I heard that there was a chance of doing a three-part series in Australia on the Great Barrier Reef actually taking David Attenborough. So you can imagine I was extremely excited, slightly petrified, but it's David Attenborough, it doesn't get better than that. So we ended up doing a three-part documentary called The Great Reef. David came on board. We did some surface filming, but we did a lot of filming in the sub. Now, at the time he was 93. it was his last official, onsite production because he was obviously stepping back, he still wanted to do the narrations.

[00:20:23] Steve: So, just step back a second. When was the first meet up?

[00:20:28] Mark Taylor: I first met David in Cairns in Australia. A taxi drove up to the ship and just seeing him walk up the gangway of the ship and greeting us all, it... was, yeah, amazing.

[00:20:43] Steve: And then, presumably there's some work to do before you jump into the sub?

[00:20:48] Mark Taylor: When you're doing a production like that, there's lots of sort of meetings and you are working out where you're going, what you're doing. There was the upstairs eating area for the guests and the VIPs and there was the crew eating area. And he didn't want to eat with the guests. He always wanted to be with the crew. He'd pop into the galley and see the girls and grab a sandwich and just so down to earth.

[00:21:15] Steve: And so it's time for the first dive. Now, these subs are pretty small. Not that easy to get in and out of. David Attenborough was 93. How did that work?

[00:21:29] Mark Taylor: These subs, because you enter them from the top, you have to sort of squat down into them and climb in and climb out. Even at 93 he didn't want any fuss, he didn't want anybody helping. He just had his knees reconstructed but he was like machine. As long as I supplied him with M&M's for the duration of the dive, so the little chocolate M&M's, he was a very happy boy.

Record breaking dive

[00:21:59] Steve: And it was on this trip with Sir David that Mark achieved another first: boldly going where no man had gone before...

[00:22:08] Mark Taylor: So the highlight of that trip with Sir David was diving down the fringe of the outer reefs, which, you know, doesn't get visited very often. And we descended down to 300 meters, which is a current record for a man dive on the Great Barrier Reef.

[00:22:28] Steve: And describe the atmosphere in the sub at times like this. Are you laughing and joking? Is it deadly serious?

[00:22:36] Mark Taylor: It's mixed. And this happens in the sub... you'll go through stages where there's lots of talking and obviously you're doing pieces to camera, but then in between there's very often quiet spells and it's not that feeling of uncomfortable quietness. Everybody's sort of reflecting and taking in the atmosphere and the environment that they're in, they're trying to take it in and sometimes it, it is a bit overwhelming. So you get these quiet spells where everybody's just like, "Wow". And you can imagine on the Great Barrier Reef, you're cruising along the top of the reef and there's just sharks all around you, turtles all around you, beautiful corals. Yeah, sometimes you're just mouth open in awe.

[00:23:26] Steve: Clearly, a very special moment in Mark's already colourful career. And, true to character, Sir David didn't quite leave the experience there.

[00:23:39] Mark Taylor: When I got home after that trip, it was sort of like a week after we'd parted, I got home and there was a parcel there with a handwritten letter, a signed copy of his book, a very, very personal letter. It was just, you know, amazing.

[00:23:59] Steve: And thinking back to being an impressionable kid diving at Lulworth Cove, pretending to be Jacques Cousteau, or, in this case, David Attenborough; to be with him on his last official on-site production, presumably that's about as good as it gets?

[00:24:17] Mark Taylor: Yeah, absolutely. It's as good as it gets and it just such a career highlight. Yeah.

[00:24:23] Steve: And those bonds we talked about?

[00:24:25] Mark Taylor: To be able to spend time with him in that sphere, it does change relationships. There's a bond that gets built.

Premiere of Great Reef

[00:24:37] Steve: And that bond was demonstrated at the launch of the Great Reef, wasn't it?

[00:24:41] Mark Taylor: Yeah I went to the premiere of the Great Reef, which was at Australia House in London. And Prince Philip was there, many celebrities and I'd flown from Australia to go there. And we watched the first episode and then there was a question and answer and the director told him that I'd flown from Australia to be there, and he stood up and saw me across a hall and started pushing chairs out the way, walked straight past Prince Philip and just came over and gave me the biggest hug, and I just stood there going, "Oh my God," and all these people are just staring at me.

[00:25:34] Steve: I think something similar happened at the premiere for Blue Planet II, didn't it? On the red carpet?

Premiere of Blue Planet II

[00:25:39] Mark Taylor: It was a blue carpet for Blue Planet II, so getting interviewed on the blue carpet and David Attenborough came up behind me and the lady interviewing me saw him and basically - you would've loved it cuz it was a great rugby move - palm into the face and pushed me out of the way to get towards David. And he almost did the same to her and walked straight past her and gave me a great big hug. And then we had a, like a two or three minute chat on the blue carpet while she was just stood there with her microphone and her mouth open. So yeah, he's an amazing, amazing person.

[00:26:27] Steve: That's a fantastic story, a great moment. David Attenborough has clearly had a tangible influence on your life. Reflect on that...

[00:26:38] Mark Taylor: One of the things I was slightly nervous about was they always say, "Never meet your hero". And I have experienced this in the past where you've built somebody up so much in your head and you finally get to meet them and you are extremely disappointed. I was immensely happy to realise that with Sir David, what you see is what you get. He is just incredible on all levels. His knowledge is amazing. His way with people is amazing. His professionalism is unbelievable. Nothing is properly scripted. It just flows.

[00:27:19] Steve: And aside from the personal experience, what will you most remember about him?

David Attenborough thoughts

[00:27:25] Mark Taylor: I knew he was dedicated, but so driven as well. Just the way he would jump in and out of the sub at 93. You know, most 50, 60 year olds struggle, and he's just so driven and so knowledgeable. on all topics.

[00:27:45] Steve: Mark has seen elements of the natural world first hand that most of us could only dream about. He's been up close and personal with some of the greatest brains who dedicated their lives to worrying about the future of our planet. And he's directly seen the contradictions of the world we live in; the beauty of the oceans, alongside increasing reminders of our effect on them through the rubbish that we deposit in them.

The future of our planet

[00:28:14] Mark Taylor: We're in a very interesting period of humanity. Part of the world are pushing very hard with environmental issues, especially plastics and things like that. But many countries, many parts of the world are not. And I get to see that first-hand. The amount of plastic in the ocean, ghost fishing equipment, which is discarded fishing equipment that's just floating around. I've seen that in highly protected marine reserves like in Galapagos. You see fishing gear everywhere and it's... it is disheartening. If we could all work together, we could do something about it, and it needs everybody join in. Otherwise, we are just gonna clog the ocean. We really are.

[00:29:03] Steve: Yeah, that's a bit of a depressing note to finish on isn't it? With regard to the future of our oceans, is your glass half full, or half empty?

[00:29:12] Mark Taylor: I'm still positive. Blue Planet was amazing because it started the plastic revolution, but it didn't reach everybody. The the ripple effect is huge, you know, billions of people have... actually watched It now, but we need to push that out into different communities. Is it doable? Yes, absolutely. And I.... feel positive that we can make a difference. That's one of the reasons why I do what I'm doing, so that I can go out there, capture it and give it to the world. This is the only way we're gonna be able to reverse this if people get to see what's going on. It's very easy to look out into the ocean and see this beautiful, blue expanse, but you have no idea what's underneath and what turmoil's going on underneath the ocean.